When a postal system was first established in this country provision was made for the carriage of the mails between the General Post Office in London and the various Post Towns on the roads radiating from London to the different parts of the country; there was no provision for the conveyance of letters locally, either in London or elsewhere, and while it was easy to send a letter from London to, say, Edinburgh or Dublin, there was no way of sending one from, say, Lambeth to Islington except by employing a special messenger. Letters for the country could be posted at certain Receiving Houses in London in 1651 or earlier, but that did not serve as a means for conveying letters from one part of London to be delivered in another the letters were merely taken from the Receiving houses to the General Post Office to be despatched thence to the country.

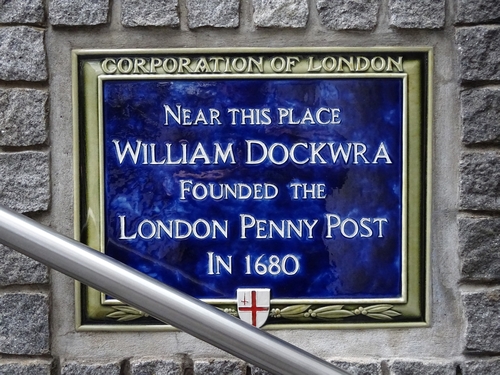

It was not through any effort on the part of the Post Office authorities that this inconvenient state of things was brought to an end. Other names have been mentioned as having prepared schemes for the local transmission of letters in London, but it is generally accepted that it was William Dockwra, a London merchant, who with certain partners in the undertaking established on March 27th 1680 'The Penny Post'; a system by which letters and parcels were carried for one penny (prepaid) from one part to another of London, Westminster and Southwark, and certain neighbouring parts.

We have a certain amount of contemporary information about this post in a book The Present State of London, by Thos. De Laune (1681) and in notices issued by Dockwra and his fellow 'undertakers', particularly one entitled 'The Practical Method of the Penny Post'. The Principal Office was as Dockwra's house in Lyme Street, and there were seven Sorting Offices and between four and five hundred Receiving Houses, at which letters were taken in to be collected later by messengers and carried to the sorting offices for delivery from them. Letters and parcels not exceeding one pound in weight, and not being of extraordinary bulk nor over £10 in value were carried between the different parts of London, Westminster, Southwark, Redriff (Rotherhithe), Wapping, Ratcliff, Lyme-house, Stepney, Poplar and Blackwall, and all other places, 'within the weekly Bills of Mortality', and the four towns of Hackney, Islington, South Newington Butts and Lambeth. There was a uniform charge of one penny which had to be prepaid, but in the case of the four 'out towns'; this only covered delivery at the Receiving Houses; if a letter was delivered to the addressee a further penny became due and had to be paid by him.

It appears that the number of deliveries daily varied from twelve in the business streets of the City and in the Inns of Court to four in the 'most remote places', an astonishing performance for such early times. Dockwra claimed that letters would be delivered to the most remote parts of the area in three hours and to the nearer parts in half that time. Letters were collected from the Receiving Houses, except in the out towns, every hour from seven in the morning till nine at night 'on post nights' - that is to say on the three nights weekly on which despatches were made by the General Post. From the 'Practical Method' circular it seems that letters put into the Receiving Houses by eight o'clock were delivered by the Penny Post the same night, except in the more remote parts such as Blackwall, Redriff, etc., and in the 'out towns'; on Post nights, when there was a collection from the Receiving Houses at nine, the letters for the General Post were taken at once to the General Post Office, but those for local delivery were held over till next morning and delivered about nine. In another part of the circular, a very wordy and confused document, eight is mentioned as the time of the first delivery; as there was a stamp showing the hour of eight in the morning this is probably the correct time, not nine. Dockwra felt it necessary to apologise for not delivery the nine o'clock letters the same night; as he says 'very late delivery of letters is a great disturbance to the Inhabitants, beside the great Toyle and Slavery that it procures to the poor Messengers'. Notice is given in the circular that the post did not 'go' on three days at Christmas, two at Easter and Whitsuntide, nor on the Thirtieth of January, the anniversary of the death of Charles I.

The collection of letters for the General Post referred to above was a considerable source of profit to Dockwra, who spoke of the great convenience of the service and pressed people to adopt it. If General Post charges had to be prepaid the money was to be deposited with the letter at the Penny Post Receiving House, the amount being endorsed on the letter, which otherwise would be returned to the Penny Post Office. Another service was the delivery of letters to carriers and coachmen, for further conveyance by them; it was announced that 2d had to be sent with each letter to be given to the carrier, etc., who otherwise would refuse to accept the letter which would be returned to the office. As this was openly advertised it seems that the conveyance of letters by carriers, etc., in certain cases was not illegal; the monopoly of the postal service did not extend to places to which no post had been established. We can well imagine that the distinction as to what was strictly legal was not always observed in practice.

It would seem that at first the 'Undertakers', as Dockwra and his partners described themselves, admitted responsibility for any loss or damage; this appears to be implied in the circular of 1681, in which for the future liability for damage is entirely repudiated, and for loss is admitted only in the case of packets fast sealed up, the contents and value plainly endorsed upon them. According to Dockwra, the knowing ones of those days had quickly realised the possibility of making fraudulent claims for damage or loss said to have been suffered in the Penny Post.

There was at first much opposition to the Penny Post on the part of the porters, who considered that it threatened to deprive them of a considerable part of their employment, and they assaulted the messengers, tore down advertisements and otherwise used violence, until they were restrained by the Law. Then there was opposition of a political kind; in those days of intrigue and plot every new device was subject to suspicion and the Penny Post was no exception, being charged with complicity in Papist plots. Despite all difficulties it is clear that the post performed a valuable public service tolerably well and in its second year it became a commercial success.

It was this success no doubt that drew on Dockwra and his friends the envious regard of the authorities. The profits of the Post Office had been, by an Act of 1663, settled on the Duke of York, subject to a yearly payment to the King of £5382.10s.0d. In 1682 actions were brought against Dockwra on behalf of the Duke (afterwards King James II) for violation of the patent of the Postmaster General in regard to carrying letters, and on November 23rd of that year judgement was given against him in the Court of King's Bench. This meant the immediate closing of the Penny Post so far as Dockwra was concerned, and it seems that for a time London was once more without any organised system of local postal communication.

That is the end of Dockwra in this book, but not the Penny Post which was started up again but this time by the Government - a Post Office notice appeared in the London gazette of November 27th 1682 announcing that the Penny Post would shortly be re-opened and a further notice in the issue of December 4th stated at the re-opening would take place on December 11th 1682....men who had worked in Dockwra's Post were invited to apply for employment in the new Penny Post.....

Source: The Local Posts of London 1680-1840 by George Brumell first published in 1938 second edition published by Alcock and Holland but no details given of the reprint. pps 8-10